Dept. Of Celebration: Drunk Monk – New Yorker

May 2, 2005

by Amy Goldwasser

There are only so many birthday-party venues where you wait around for the guest of honor in your socks. One of them is a Buddhist kung-fu temple. One night not long ago, about two hundred people left their shoes outside the door of the U.S.A. Shaolin Temple, on lower Broadway, and shuffled inside to await the arrival of Sifu Shi Yan Ming, a thirty-fourth-generation Shaolin fighting monk, whose forty-first birthday they intended to celebrate by drinking vast quantities of beer—or “special water,” as Yan Ming likes to say.

The celebrants spanned an easy range of age, race, profession, and style: deli clerk, baby, Wesley Snipes, sociology professor, Masta Killa. The RZA, of the Wu-Tang Clan, who spent much of his childhood skipping school to watch kung-fu movies in Times Square, was there, wearing a Staten Island baseball jacket and cap. In a room where hair was fairly unpopular, you could spot Jim Jarmusch’s tall, fluffy white head.

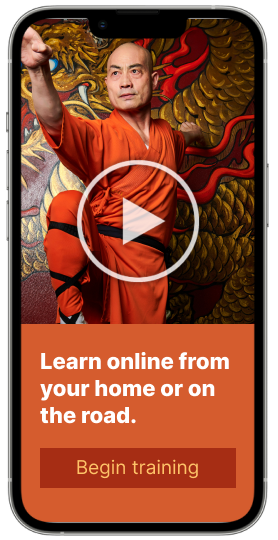

The students, dozens of whom were planning to stage a performance for their master (or sifu), were wearing orange or navy monk’s robes. As they waited, they blithely performed amazing feats.Two women rolled over each other’s back; another cartwheeled, no hands; a young man with long dreadlocks doodled in the air with a broadsword; another, head shaved, did a standing flip. The d.j., whose booth was in front of the sword rack, was wearing a yellow T-shirt bearing the temple’s slogan in red: “More Chi! Train Harder!”

This is something Yan Ming yells all the time—along with “Merry Christmas!” and “Happy New Year!” In his view, every day is a cause for celebration, and everybody is “handsome.” Before he was born, two brothers and one sister died of starvation. When Yan Ming fell extremely ill as a young child, his parents took him to the Shaolin Temple, in Henan Province, the birthplace of Ch’an Buddhism, and left him there, in the hope that Buddha might save his life. Under the monks’ tutelage, the boy became a master of Shaolin kung fu. By the time he was seventeen, he had been trained to withstand a full-force strike to the groin. He can lick red-hot iron shovels, break bricks with his skull, fly aboveground upside down in full splits, and sleep standing on one leg. In 1992, in San Francisco, while on the first Shaolin Temple monks’ tour of the United States, he defected and made his way to New York.

By 1995, Yan Ming had opened a temple on the Bowery, a cramped space without heat or electricity. That same year, he met Sophia Chang, a Korean-Canadian who was the manager of Ol’ Dirty Bastard, a member of the Wu-Tang Clan. (Yan Ming and Chang have two children. Shaolin monks have an exemption, granted by an emperor whom they protected during the Tang dynasty, that effectively permits meat, alcohol, and sex.) She introduced him to the RZA at a record-release party. The Wu-Tang Clan’s delight at meeting a real Shaolin monk lent Yan Ming some hip-hop cred, and before long he had moved to a bigger space, where he began training the Wu and many others in the Shaolin way.

His arrival at the birthday party was signalled by a burst of applause and shouts of the Buddhist greeting “Amituofo!” He entered from the stairwell wearing Comme des Garçons street clothes: navy shirt with an oversized black zipper and black pants. He took a seat front and center. The d.j. started a break beat, and the performance began. The students spun through choreographed fight sets, animal forms (eagle, snake, tiger, praying mantis), palm strikes, flying and spinning kicks, cartwheels, splits. When it was over, Yan Ming stood and said wholeheartedly, “I’m the luckiest sifu in the whole world!” Then he grinned. “Now, are you ready to train harder with the special water?”

The students took turns manning the bar—beer, sake, champagne (“very special water”). Nearby, friends made introductions to Yan Ming: “Yo yo, this is Pink,” and, “This is my sexy bodyguard.” The Shaolin tradition is to salute with the right hand, but, since Yan Ming was holding a bottle of champagne with that one, he raised his left. He filled people’s paper cups: “Merry Christmas!” Chang, whose head was shaved, called out, “Dave Chappelle’s been down there buzzing! Can someone go down and let him in? Amituofo.”

Out on the dance floor, Yan Ming moved, with almost any-guy imprecision, to the strains of “Mothafucka, what’s wrong with you?” and “Can I kick it?” A dance circle formed, the monk staying clear of the center, and the kung-fu battles—like nonverbal rap battles—escalated to the point where one man jumped clear over the head of another.

Around midnight, the birthday cake came out, decorated with the words “Happy Birthday Handsome.” By this time, Yan Ming had begun to lose his English. “Cut the cake! Cut the cake!” everyone chanted. A Wu-Tang Shaolin song played. Sifu Shi Yan Ming raised his left arm and, with full concentration, sliced the cake down the middle with a split-second kung-fu chop.

A few of the last guests to leave, hours later, found Yan Ming out in the rain on Broadway, buzzing to get back in. Bits of cake were stuck to his cheek. “Happy New Year!” he called out, as they held the door for him. “You are so handsome. Happy Birthday!”