HIP-HOP MONK

December 1, 1997

Paper Magazine by Clara Young

Paper Magazine by Clara Young

Shaolin Temple Master Shi Yan Ming, who came to New York from China in 1992, is probably the only green-card holder who can dangle a 50 pound weight from his testicles. A 34th-generation Shaolin Temple monk, he can also shatter stones with his head, poke his fingers through a wall and lick a red-hot shovel. But the most amazing thing about this very humble monk is simply the way he moves. Shi Yan Ming, a “Living Treasure of China”, moves with more grace, speed and power than any other man in America. Today, Shi Yan Ming, 33, is founder and abbot of the U.S.A. Shaolin Temple in downtown Manhattan, where he teaches kung fu, tai chi, chi kung, Buddhism and meditation. His students range from university professors to, curiously enough, many of the cut masters and grand masters of the hip-hop nation, like Jeru the Damaja, Tricky and, of course, the Wu-Tang Clan, who call their home base, Staten Island, “Shaolin” and practically own the patent on martial arts-driven lyrics.

The temple is actually two long rooms on the third floor of a building on Broadway and Bond Street, accessed by an old freight elevator. To someone who grew up watching David Carradine try to snatch the pebble from his master’s hand on Kung Fu, it doesn’t look much like a Shaolin temple, but the large Buddhist altar next to the front windows, the “Rules of Conduct” posted on the wall (“Do not sit with your back to the altar”, “Do not put Buddhist literature on the floor,” “Do whatever you can to help others”) and the students’ obvious devotion to Shifu (“Master” in Mandarin) show that it is a place of serious study and discipline. It is certainly a much better facility than Shi Yan Ming’s first Manhattan temple, above a grocery store in Chinatown, where the ceilings were so low that he and his students couldn’t jump or swing weapons.

But it is still light years away from Shi Yan Ming’s home, the original Shaolin Temple, the legendary fountain of martial arts at the foot of Mount Song in northern China that was established 1,500 years ago by the Indian monk Batuo. Shi Yan Ming entered the Shaolin monastery when he was five and spent the next 25 years absorbing complex kung fu fighting forms and Chan Buddhism – the more jovial branch, which tolerates drinking alcohol and eating meat and preaches non-violence. Like the heroes of celluloid kung fu classics, he and his fellow disciples slept on wooden planks, got up at 4 every morning, meditated and followed the intensive physical and spiritual training that enabled Shi Yan Ming to master several martial arts and win a score of Chinese national titles. Now he continues that life though slightly modified – at his new temple and in a small apartment in Greenwich Village.

Shi Yan Ming’s mission is to build an authentic Shaolin temple in the United States: “A place where people can come and live,” he says. “Open all day. Just like the Shaolin temple in China. Everyone needs kung fu. Not just Chinese. That’s why I’m here now. Everyone must learn. Everyone needs training.” “Training” is the key word in Shi Yan Ming’s vocabulary. He uses it to describe just about everything, including the most banal aspects of daily life, like washing dishes or watching television. Or drinking beer. Within seconds of meeting Shi Yan Ming for the first time, he thrusts a bottle of Corona into my hand. “Training!” he says, thumping himself hard on the chest. “Chi come out!” (Chi, Mandarin for “life force,” is the other key term in Yan Ming’s lexicon.) He particularly likes beer, which he calls “special water,” but he also has a soft spot for wine (“French special water”) and champagne (“very special French water”). These, along with the outrageously spicy noodles he thrives on, are an important part of his daily regimen.

This notion of training is difficult for guilt-ridden, unhealthily health-obsessed Westerners to fathom. It’s not training in the sense of preparing for some goal. It seems to have more to do with constantly growing and learning. “Learning comes through enjoying life”, he explains. “You must be happy, or you have nothing.” While Shi Yan Ming is a taskmaster in the temple, relentlessly pushing his students through complex routines, he is otherwise delightfully playful. “Everyday is a holiday,” he responds when asked about his basic approach to life. “Everyday different. Merry Christmas!” Has life in the Big Apple sapped any of Shi Yan Ming’s Buddhist serenity and kung fu rigor? “Nothing has changed in my life”, he answers firmly. “I am at home in America. A Buddhist monk is at home everywhere.”

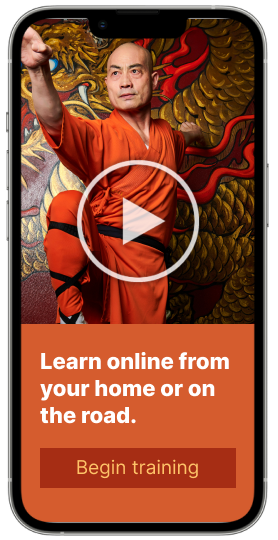

But things have obviously changed in many ways. His mission of opening an authentic temple in America has drawn him into the decidedly non-Buddhist world of commerce, marketing and media promotion. The temple walls are lined with autographed photos of Shi Yan Ming standing next to celebrities like Oliver Stone, John Woo, Meg Ryan, Jackie Chan and countless hip-hop stars. But it is the unexpected collusion between hip-hop music and kung fu films that may generate the most media interest in his mission. He is revered by artists like Wu-Tang’s RZA, whose autographed picture in the temple says it all: “To Sifu Shi Yan Ming: There are not many men I can or will call ‘Master.’ I say it to you with the utmost respect. All art is now martial to me. Your friend and student, the Rza, the Wu-Tang.” The Manhattan monk is getting busy: entertaining film offers, organizing demonstrations at the temple, coming out with his own video and going online with his own slick-looking Web site (www.usashaolintemple.org). It seems that a Buddhist monk is, indeed, at home everywhere – even in cyberspace. U.S.A. Shaolin Temple, 678 Broadway, 212-358-7876.

(The USA Shaolin Temple has since moved to 446 Broadway, 2nd Floor.)